Fated

In Greek Myth, the Fates were the three goddesses who decided, well, our fate. They were imagined as spinners and weavers, since, in the past, the making of cloth from wool or flax, was a job that occupied most women for most of their days.

Clotho spun the thread of our lives, on a spindle. Her name means 'the Spinner.' What she spun the thread from, I'm not sure. Dreams? Time?

She was especially associated with the present. That's her, in red, on the right, holding her spindle.

Lachesis, in the centre, measured the length of each individual life. Her name has been translated as 'the Allotter' and she concerned herself mostly with the future.

When Lachesis had decided on the length of a life, it was Atropos who ended it, snipping through its thread with her shears. She's on the left, an older woman in sober black. Her name meant 'the Unturning' or 'the Inflexible' and her special concern was the past. I suppose she sent you into the past, to join your ancestors.

The woman lying at their feet must be someone who has met her fate.

The power of the Fates, or fate, was so great that not even the King of the Gods, Zeus, could alter their decisions.

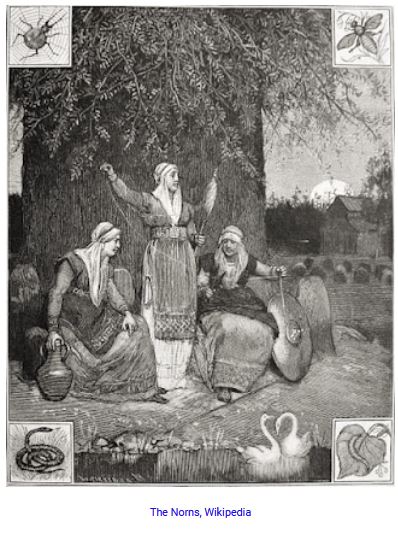

In Norse Mythology, a trio of giantesses, the Norns, fill the place of the Fates and are, perhaps, even scarier. They are to be found near the well at the foot of the World Tree and they water its roots.

They weren't worshipped, as far as we know. They wove the web of our fate and the world's fate and they were implacable, so there was nothing to be gained by making them offerings or pleading with them. The Norns were also weavers but they were imagined as 'weaving a web' -- that is, weaving a great tapestry on a loom. All the lives on earth were simply threads in their great web, intertwining, knotted, cut short, part of an immense, complex pattern.

In one saga an unlucky man has a vision of Valkyries weaving 'the web of war' on a great loom. The warp and weft are bloody guts, the

shuttle a spear, and the loom-weights severed heads.

The names of the more peaceable Norns were Urðr, Verðandi and Skuld -- pronounced something like Oorther, Veradunti and Scald. There's a lot of scholarly disagreement (as usual) about what the names meant, but one idea is that Urðr meant 'That Which Has Happened'', Verðandi means, 'That Which Is Happening' and Skuld means, 'That Which Is Yet To Be.'

Given this knowledge of Past, Present and Future, the Norns sometimes rocked up to the celebrations at a birth, to give notice of what the

baby's fate was to be, for good or ill. They lingered on into the Christian period as the good and bad fairies who turn up to foretell that one child will prick her finger on -- what else?

-- a spinning-wheel and fall asleep for a hundred years. Or that a baby boy born in poverty will marry a king's daughter despite everything the king can do to prevent it. In fact, his efforts to

prevent the marriage are exactly what brings it about. As so often. That's Fate for you.

A bit unfair to call the Norns 'wicked fairies' though. They were only letting people know the weird woven for them. If people had learned to just accept it, they'd have saved themselves a lot of time and trouble.

I didn't set out to include the Fates or the Norns in my book Telling Tales, but obviously, it was fated that they should turn up.

Initially, it was to be a collection of retold folk tales, set in a frame that described neighbours helping each other out. A bride needs a whole load of new clothes, towels and sheets sewing -- so the neighbouring women gather in her house and chat and tell stories as they do the work.

A girl is about to leave home, to take up work as a servant -- and the neighbours gather to see her off and wish her well.

There's a death, and while the bereaved family attend the funeral, some women stay behind, to make sure there's plenty for the returning mourners to eat and drink.

And, when a new baby is born, the neighbouring women come along to look after the older children and make sure there are meals cooked for them.

I had the stories told on these occasions because I was interested by the idea that certain stories were told only on certain occasions: only at funerals or only at weddings, as a sort of protective spell or a charm to bring good luck. But managing a large cast of anonymous characters, popping in and out of houses to tell stories, began to seem rather clumsy.

It seemed better to have one or two named characters, who would tell all the stories -- or how about three, since things in folk-tale

always come in threes? And make the three women, since they were performing household tasks -- and who does most of that, even now?

Three women, attending on births, deaths, marriages and youngsters leaving home? What names suggested themselves for them?

Clotho, the spinner, became Clo...

"Now, who’ll tell us a story?”

“It happened once,” said Clo. “that there was a farmer who loved his wife, loved her deep and dear, and when her was to

have his babby, there was nothing in this world could make him happier. But the woman had hard time of it. The babby was born alive. The mother

died.”

“Oh, Clo, you could tell a happier story!”

“Ssh!”

“Listen. Go on, Clo...”

Lachesis, the allotter, became Letty...

“So cheer up, my lamb,” said Letty and cuddled Polly again. “You’ll make your little fortune and find your squire—”

“I never found neither,” said Granny Shearing.

“Oh, you shut up,” said Letty. “Don’t you listen to her, my love. Her’s had a good long life—”

“Hardship and heartache,” said Granny Shearing. “If I told you my story, I’d have you all sobbing.”

“Don’t you mind her,” Letty said. “Her’s had her moments, her’s kicked her heels up.”

“I wouldn’t change any of it,” Granny Shearing admitted.

“Auntie Letty,” Polly said, “will you tell a story?”

Letty sat thoughtfully for a while. “The only one I can think of just now is this one…”

“This happened years ago, when times was hard. There was no work and no money and people was living on Waterloo porridge— that’s what the soldiers et on the battlefield at Waterloo when they couldn’t build no fires to cook. It’s just flour or oatmeal stirred into cold water. People was so hard up back then that they hadn’t got no money to buy coal or wood for fires to cook food, see, and they couldn’t afford nothing but flour. Miserable times. Don’t let nobody tell you about the ‘good old days’ when everything was wonderful and everybody was happy. There was never any such time.

“Anyroad, there was these two blokes— they was called Jack and Joe— and they left their wives and children behind and set out on the tramp, tramp, tramp, to find work...

And Atropos, the unturning, became Granny Shearing.

Old Peter, in his coffin, was carried away from his house on the shoulders of six men. His widow followed behind, with her sons and daughters and their families. The sun shone. Flowers swayed among the thick greenery of the hedges. Birds called and whistled from the trees.

Three neighbours stayed behind at Peter’s house, to make ready the food and brew the tea for when the mourners returned. Sunlight, angling through the kitchen window, gleamed on the thin edge of a milk jug and shone dully on the iron base of a pan hanging from a hook.

A long carving knife flashed in Granny Shearing’s hand as she cut slices of bread and piled them on a white platter, while brown crumbs scattered on the cloth. At the table’s other end, the cloth was folded back, to show the scrubbed wood. There Clo worked, weaving strips of dough into small plaited loaves, to be sprinkled with tiny black poppy seeds and baked. Letty counted the plates, cups and glasses, to be sure there were enough.

“I remember,” said Granny Shearing, “when my mother’s second cousin died… A lot of folk went along to her lykewake. That’s where the body’s laid out and people light candles round it and sit up all night, watching.

“Among them that went there was a couple of young lasses, Katie and Mary. They’d never been to a lykewake afore. Didn’t know what to expect..."